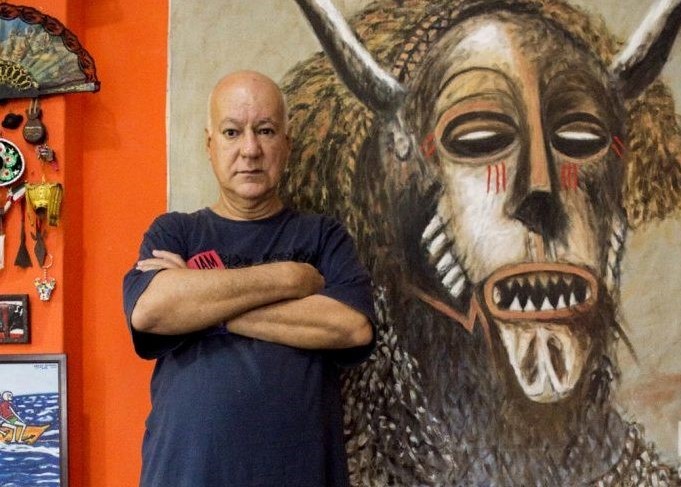

If there is an image of a bull in a Cuban painting – often portrayed as a powerful, majestic symbol of struggle – chances are that the work has been created by Rafael Zarza who has recently won Cuba’s most prestigious award the National Visual Arts Prize for 2020. Lesbia Vent Dumois, president of the jury that awarded the prize, recognised Zarza’s accomplishments well beyond the genre of printmaking for which he is best known, to include installations, drawings and above all, painting and also his conceptual contributions, in terms of representation, questioning and re-creation of Cuban social and cultural life.

Born 2 October 1944, Zarza studied at the San Alejandro Arts Academy during the tumultuous early years of the Revolution between 1959 and 1963, and from 1965 until 1996, he was an active member of Havana’s renowned Experimental Graphic Workshop (Taller de la Gráfica Experimental) where he worked alongside artists such as Umberto Peña, Antonia Eiriz, and Raúl Martínez. Zarza enriched his lithographic images with parodies of icons and symbols of universal art (Warhol, Rubens, crucifixions) and the pop world (The Beatles, Led Zeppelin). It was during the 60s that he started working with the image of the bull which for Zarza “was the symbol of freedom, because it is an animal that dies fighting, that dies in the ring.”

A 1968 exhibition sponsored by Casa de las Americas was a turning point in his work. Based on a classical myth where Zeus is portrayed as a cow, his lithographic work El Rapto de Europa (The Abduction of Europa) won the Portinari prize. Zarza later stated this was the emergence of “the seed of my entire pictorial world, which is characterized by a certain irony.”

The bull, the cow, and the bullfight that became metaphors in his work were initially associated with the Spanish roots of Cuban culture. Referring to one of his best-known series, the ‘Tauros-retratos’[Bull-portraits] and ‘Vaca-retratos’ [Cow-portraits], Zarza explained how he “worked with the faces of the Spanish colonialists, that is to say, people who were very reluctant and reactionary toward Cuban culture … I usurped their portraits and attacked them and placed horns on them and turned them into oxen … Cuba never submitted and this series is a way – my way – of paying tribute to all those men and women who, throughout our history, did not give in.”

However, Zarza did not limit his exploration of Cuban identity and culture to metaphors drawn from its Spanish colonial roots. When he was in Angola on an internationalist mission teaching art in 1977, he said “I started to study the masks – of great beauty and strength – and to try to combine the African with European influences, and I incorporated all that wealth to my world of cattle and oxen … Africa was summed up in the African masks’ smell of the dancer, the taste, the dust… and also elements that make up the Cuban nationality, which is a legacy of the Black continent.” This African interest was reinforced with his artistic residency in Kenya in 2003.

Over the decades of his career, one thing that characterises Zarza’s work is openness to wide-ranging influences – from religious and classical subjects, the work of other artists such as Vincent Van Gogh or Wifredo Lam, or the eroticism of 15th century Japanese Shunga art in more recent years. One of Zarza’s best known works on display at Cuba’s National Museum of Fine Arts is a large canvas, The Great Fascist (1973) featuring a decorated military bison, executed in Zarza’s signature palette of strong reds and black. The work condemned Latin American totalitarianism at the time of the coup d’état against Chile’s Allende.

Throughout his career as an artist, Zarza has shown an astonishing ability to keep enriching such a strong symbol as the bull. He has accomplished this at a formal level by incorporating elements like texts and photography and by adopting a range of artistic languages from expressionism to pop art. His use of erotic and religious imagery was not always liked or approved for public view in the 1970s, but the constants in his work are his use of parody, humour, wit and appropriation; his technical expertise; and his determination to remain true to his individual artistic impulses.

Dr Doreen Weppler-Grogan for Cuba50

You must be logged in to post a comment.