As a major exhibition of Cuban poster art goes on display in London until January 2020, Cuban art specialist Dodie Weppler-Grogan examines the history behind the genre.

Poster art appeared in the first days of the Revolution, and by 1965 the golden age of the Cuban poster had arrived. In the single year of 1972 around five million posters were made. The high professional standards of Cuba’s posters and other graphic arts impressed art specialists around the world. The variety and exuberance of the styles, as well as the skill in reducing the theme of each poster to its essentials, was remarkable.

This new genre of art and its unique graphic style was born of necessity. In the early tumultuous days, there was a burning need to communicate with the Cuban people about each development as the Revolution advanced. Posters were especially appropriate for this task as they were easily transportable and could be displayed on billboards. It was also little trouble to put up new ones, which was often essential with the rapid changes underway in society.

These features were important because posters had a new function. Unlike the graphic arts introduced to Cuba by the US before the Revolution, the new poster aimed to engage the viewer as a thinking person, not as a passive consumer of commodities. The posters of past days with easily digested sound bites were rejected –instead, the goal was to “raise and complicate consciousness – the highest aim of the Revolution itself”.

While communication was fundamental, it was equally important to view the poster as a means to help refine the popular taste and sensibility of the Cuban people. The days when the visual arts were the preserve of the wealthy few were over, and the cultural policy of the Revolution called for art created for and by the people. While the Literacy Campaign taught the people to read and write, the Cuban poster became the Revolution’s visual code.

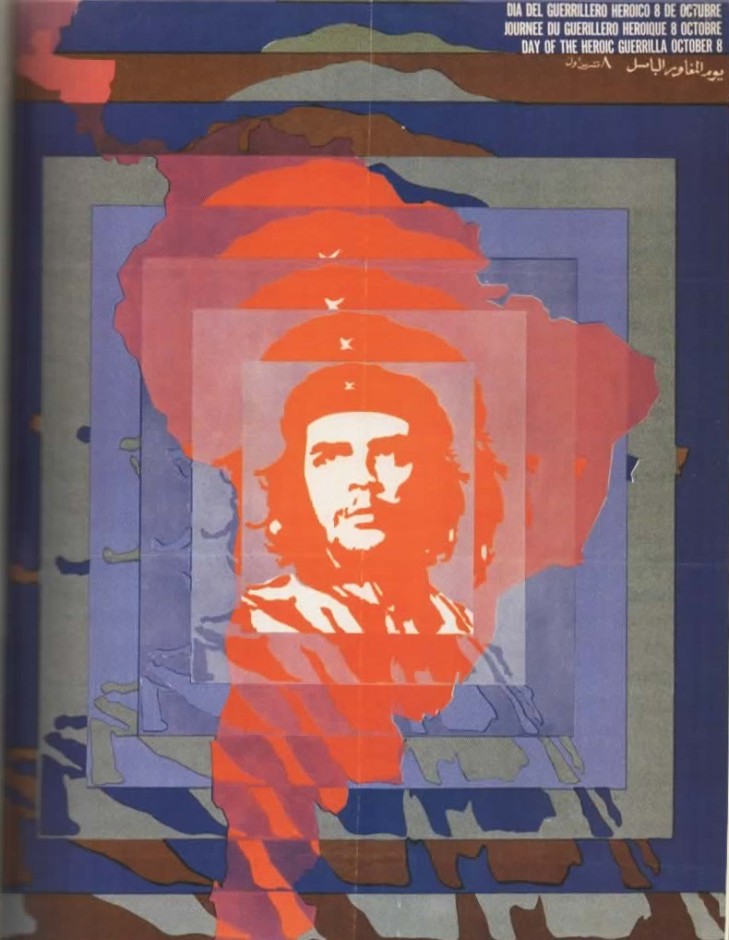

Cuban artists joined graphic designers and illustrators and set out to create posters with attributes such as “beauty, audacity, power, and knowledge”– bringing ‘fine arts’ to the people, as Cuban art historian Adelaide de Juan put it. A raft of designers including Elena Serrano, Felix Beltran, Raúl Martínez, Eduardo Muñoz Bachs, Alfredo Rostgaard, Gladys Acosta, Avila and José Gomez (Frémez) – to name but a few – created an outstanding body of work combining cultural values and an ability to inform. But the poster was not only about the skills of the artists. An integral element was how the thinking and open-minded individual, the “new man” in Che’s words, would understand the multi-layered meaning of each poster.

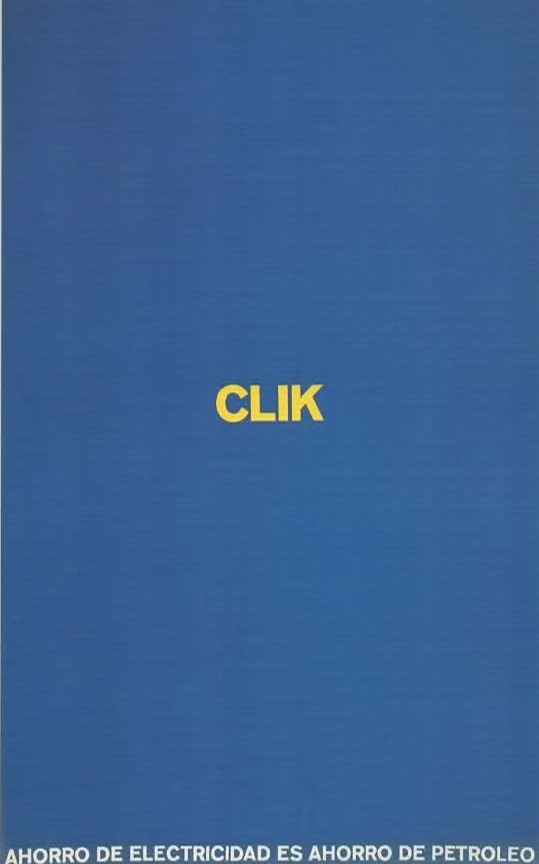

Posters were useful in every sphere. They advertised mobile medical teams, encouraged people to save electricity, celebrated contemporary and past heroic struggles, monitored sugar production, promoted women’s liberation, advertised the latest films or ballet productions, and proclaimed international solidarity. The optimism and vibrancy of the new society is evident. Their diversity contrasted sharply with the socialist realist aesthetic, which had been imposed in the Soviet Union in the 1930s but was resisted in Cuba. Instead, an amazing range of artistic languages flourished – including socialist realist art, but also constructivism, surrealism, op art, cubism, collage, and countless others. However, it was pop art that became synonymous with many of the best-known posters.

The work of Raúl Martínez provides a good example. He often utilised the familiar grid layout and repetition of the American pop art of Andy Warhol, but in Cuba it was a quite different aesthetic. Martínez did not share Warhol’s interest in the commodification of factory-made everyday objects. He was more interested in expressing a new revolutionary ‘cubanía’ – a people united around the highest ideals and ethical standards. So it was not Campbell soup tins for Martínez – instead he turned for inspiration to the people of Cuba and their heroes.

One work by Martínez – his poster for the Humberto Solas film ‘Lucia’ – is emblematic of the fresh and integrated approach of ICAIC, the Film Institute, which had one of the finest poster departments. In the pre-revolutionary movie industry dominated by US firms, the ‘Hollywood star’ poster was ubiquitous. In contrast, Martínez’s work was created as an integral part of the overall artistry of the film: amongst several interlocking elements, the three images of ‘Lucia’ in the poster actually correspond to the three vignettes of womanhood featured in the film.

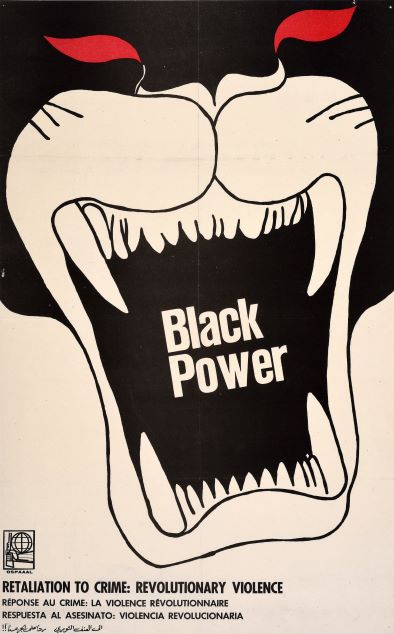

Other institutions in Cuba had their own poster production teams and, alongside ICAIC, some of the most innovative posters appeared in ‘Tricontinental’, the newspaper of OSPAAAL (Organisation for Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America) that was distributed worldwide. While specific styles sometimes became associated with posters from particular organisations, all were colourful and shared a common iconography – the dollar sign, machetes, Uncle Sam, stylised flags. The production technique varied. OSPAAAL posters were printed in offset lithography, but for posters displayed in Cuba silk-screening was also used. Expensive lithographic equipment was scarce and it was possible to produce large quantities of posters with little deterioration of the silk screen equipment.

Poster Art was an outstanding artistic achievement and it is easy to see why it is celebrated, not only for its cultural values, but also as an important visual chronicle of the early years of the Cuban Revolution. The outrage is that, thanks to the blockade, the messages of the posters – against US imperialism, appeals to save electricity, and many others – remain just as relevant today.

‘Designed in Cuba: Cold War Graphics’, an exhibition of OSPAAAL posters, runs at London’s House of Illustration Gallery until 19 January 2020. Details here.

This article appeared in CubaSi Autumn 2019 magazine for Cuba Solidarity Campaign.

1 thoughts

Comments are closed.