Ghost Towns Are Being Resurrected as Tourist Destinations

Formerly prosperous ghost towns are left to crumble—but some of them live a second life as vacation spots.

Once upon a time, the tiny town of Shaniko in north-central Oregon was not so tiny. Around the turn of the century, this was the wool capital of the world, thanks to its thriving sheep farming community and shipping position along a Western railroad. But as is the case with many boomtowns, Shaniko suffered hardships—some natural, some economic—that rendered this once-bountiful community a dusty relic of its former self. It’s a tale as old as time in the US: Industries shift, populations wane, and ghost towns emerge.

Shaniko—and ghost towns like it across the country—may be a vestige of a prosperous past, but as a result of ghost town tourism, these tumbleweed-trodden boondocks are finding new life as time capsules of yesteryear. Some come for the preserved-in-time kitsch, some for the solitude, and others for the prospect of actual ghosts—no matter the motivation, ghost towns captivate as offbeat tourist destinations. Some, like Shaniko, work to foster tourism, while more remote towns have less infrastructure and accessibility. The gamut is wide, and when threading the ethical needle between preservation and tourism, the nuances far outnumber the people in these oft-abandoned locales.

From wool to dust

The saga of Shaniko is one mirrored by many a ghost town. These are communities that once boomed, but collapsed once resources waned and the developing world left them in the dust. For Shaniko, which saw $5 million in wool sales in 1904, the demise was multifaceted, due to the construction of a diverting railroad in much-larger Bend in 1911, a fire that ravaged its buildings during that same downturn, and a great flood in the ‘60s. Rail service to Shaniko ceased in the 1930s, and it devolved into a smattering of turn-of-the-century buildings and an eerie sense of quiet. What remains might not sound like much, but it’s catnip to macabre-minded travelers looking for an immersive blast from the past. Especially now that the historic Shaniko Hotel just reopened after a 16-year-long closure, capitalizing on that catnip.

Once a beacon of prestige, this was the first building in town to boast electricity and indoor plumbing, built by the Columbia Southern Railway. But as rail service ended, the hotel’s status ebbed and flowed, with the building temporarily serving as a care facility for people with cognitive issues before being foreclosed and sitting dormant for years. Now run by the Fire Department Board of Shaniko, it emerged anew in August, 2023, a harbinger of ongoing ghost town tourism to come.

“Ghost towns are categorized in three ways.” That’s the word according to AlexSandra Conway, manager of the Shaniko Hotel. “Nothing but land, land and some buildings but no people, and land with some buildings and some people. Shaniko is the third.”

It’s the allure of the paranormal—and the innately unnerving atmosphere of these largely abandoned places—that see a path forward for towns previously left in shambles. As Conway explains, “there are a lot more ghosts than people that live here,” noting that the hotel itself has several, like a little girl named Amelia who likes to roll her ball down the halls, or Frank the maintenance guy, who folds and unfolds ladders.

“People come here for the novelty and reputation of the town,” she says. “It’s also nostalgic, because a lot of older people have heard about it or visited in the past, so it’s like checking on an old friend.” As for younger people, she says, they “hear the novelty aspect of a ghost town, not really knowing what to expect or understanding the deep rich history of the town.”

So what can you expect in Shaniko? There’s an antique store, a small museum, the original schoolhouse, a post office, and the original wool barn, albeit about one third of its former size. There’s also a vintage ice cream shop, temporarily housed within the hotel because a truck drove through its storefront, since this town can’t catch a break.

The hotel itself is the main draw—a return to form for the town’s original gem. Built out of bricks, its 38 rooms hosted cowhands and ranchers. Today, its former glory has been revived, with arched windows in the lobby, period-appropriate furniture, 17 expanded rooms, and one suite with a jetted tub. The ice cream pop-up is attached to the lobby in a former bank space, where a teller was once shot and killed in a robbery, because of course. They’re working on turning that space into a saloon.

The hotel’s reception bodes well for its success. “Everyone is thrilled that this beautiful grand-lady is open and you can come visit and see inside,” explains Conway. “We were booked on opening weekend, and it’s been slowly increasing as more word gets out.”

Such is the evolution, devolution, and renaissance of the American ghost town. While some, like Shaniko, have the roots and the tenacity to fuel ghost town tourism, others find themselves engaged in a more delicate dance.

Leave no trace

In addition to the different categories of ghost towns Conway describes, these desolate communities also span the spectrum in terms of tourism capabilities—or lack thereof. Towns like Shaniko have the buildings to accommodate, while others are so run-down that crumbling buildings are unsafe to enter—or the towns literally look like wilderness.

According to Byron Folwell, Boise-based architect and preservationist, due diligence is first-and-foremost. “I would never say any of them should be avoided, but the rules of engagement are very different,” he explains. “We have a number of places in Idaho that are set up for tourism, in some respect, for people who want to visit ghost towns.” He describes “entry-level” ghost towns, like Idaho City and Silver City, which are more accessible via roads and have services and accommodations around, as well as historic structures and active museums. There’s a middle-tier, like the town of Atlanta, which is harder to get to, has fewer services, and scant structures. Then there are the most intense ghost towns, so remote that they may not resemble a town at all. “If you’re able to find them on a map and a place to stay nearby, it usually takes a couple hours to drive to those locations from a nearby town,” says Folwell. “You can plan a weekend trip, but you’re gonna need a 4x4, and you may need to hike in, because roads may not be maintained.”

The rules of engagement here, he notes, are a “leave no trace” approach. “People in Idaho generally favor the sharing of our history as long as you don’t go in and take elements from those locations or cause disruption to those spaces.”

What fuels ghost town tourism?

A core part of the ghost town appeal, aside from potential hauntings for ghost-hunters, is the singular Americana. “I grew up in Southern California, and as a kid we used to explore all over as a family,” recalls Gary B. Speck, author of ghost town books like Dust in the Wind: A Guide to American Ghost Towns and Ghost Towns: Yesterday & Today. “But it wasn’t until 1968, on a family road trip through the California Gold Rush Country when I suddenly wanted to learn more about some of those towns we were visiting. I got bit by the ghost town bug and a life-time passion was born.”

People like Speck are the reason that the Shaniko Hotel has poured such efforts into restoration. “You come here and you step back in time,” says Conway, citing everything from its vintage cash register to in-the-works period uniforms for the staff. “You’re gonna walk in and feel instantly transported back to 1900 during the heyday of Shaniko.”

From an economic perspective, ghost towns can be a boon to regional tourism, too.

“Ghost towns are one of those buzz words that get people's interest piqued,” says Ryan Hauck, executive director of the Park County Travel Council, otherwise known as Cody Yellowstone. For his region, that means Kirwin, an old mining settlement in the remote wilds of Wyoming’s Shoshone National Forest, which topped out at around 200 residents before avalanches triggered an exodus in the early 1900s. The draw is the opportunity to experience a mining settlement frozen in time, replete with weathered wood buildings deep in the Absaroka Mountains. Although barely 60 miles south of well-traveled Cody, it’s a trek to visit, but one that tourism officials encourage—with the proper preparations, like off-road vehicles and bear spray.

Once there, travelers discover a ghost town with about a dozen historic buildings to explore, and nearby companies like Kirwin Rides that take trekkers on off-road adventures. There’s also a 3/4-mile hike to the remnants of the summer cabin Amelia Earhart was building when she went missing, in case the rest of Kirwin wasn’t ghostly enough.

According to some ghost town enthusiasts, there should be more of this type of regional marketing being done for places like Kirwin. As Speck explains, this is too often not the case. Examples include “forgotten ghost towns” that are only visited by folks who go out of their way, and historic old towns clinging to life. Notable exceptions, he says, include places like Barstow, California, which plays up the fact that the old silver mining town of Calico is nearby.

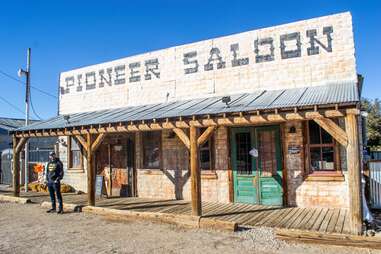

“Touristy ‘ghost towns’ are the ones with very active chambers of commerce begging travelers to come ‘see where XYZ happened’ or ‘visit the infamous XYZ saloon,” Speck says, pointing to places like Virginia City, Nevada, and Deadwood, South Dakota. “Despite the hoopla, and glitzy exterior, they really are historic towns with historical bones.”

Ruin in place

The crux of preservation philosophy, as Folwell explains, is called “ruin in place.” And it’s a key factor in those “leave no trace” principles of visitation. “In a city or town that is inhabited, it can be quite different from preservation work, or lack thereof, in a ghost town,” Folwell explains. “In cities, if it’s intended to be occupied as a space, other than a museum, and if there’s a historic district and it’s on the National Register of Historic Places, there are federal protection guidelines that protect the integrity of those buildings.”

In a ghost town, not so much. “If it’s an unincorporated area, as many in Idaho are now, and if it’s been abandoned, then there are no laws or statutes protecting those areas, because they don’t necessarily belong to anyone.” Therefore these ghosts towns, under the care and keeping of no one, tend to simply ruin in place. Per Folwell, “It’s the process by which only the most durable materials are able to last.”

The results are double-edged: while unmaintained towns provide a unique historical snapshot, sometimes they’ve crumbled into remnants that don’t resemble much of anything. “Some, all that’s left are stone foundations, or charcoal kilns where silver and gold smelting took place.” Preservation of ghost towns, Folwell notes, is unregulated in these remote locales. While somewhat inhabited towns like Atlanta receive preservation from the few folks who live there, the truly ghostly ones approach a different fate.

Speck says the key to visiting these towns, regardless of preservation, is responsibility. According to his ghost town code of ethics, this means do not trespass where properties are marked, do not vandalize (including taking “souvenirs”), respect residents’ properties, and abide by posted signs.“Above all, treat residents with respect, and where they like to talk, listen to the history they share.”

Be it a maintained community like Shaniko, an adventure haven like Kirwin, or the abandoned nether reaches of Idaho towns like Three Creek and Wickahoney, ghost towns are unique Americana that serve as time capsules to another era.

“Ghost towns work for people who are receptive to what they can tell you about themselves and about America,” describes Folwell. “These places are novel, and people get a lot out of thinking about history and the passage of time.”

The blurb on the back cover of Speck’s book, Ghost Towns: Yesterday & Today, sums it up nicely: “Ghost towns are magical places. More than empty buildings, more than decayed curtains flapping in empty windows, more than tumbleweeds rolling down empty streets, they were living communities of people… ghost towns are life interrupted.” Speck adds, “I feel strongly that what drives most people who visit ghost towns is that they give us visitors a sense of belonging and a tangible way to touch the past.”

Be it a return to boomtown heyday at an Oregonian hotel or a hike to Amelia Earhart’s cabin, touching the past—when handled carefully and with reverence—can be a magical thing indeed.